Tisha B’Av and Devarim (Deuteronomy)

by Dolores Moran

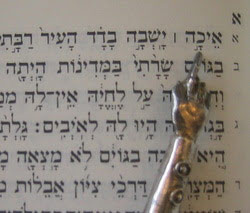

This Shabbat the scroll was opened to the book of Devarim. Parasha Devarim is always read on Shabbat Chazon (“Sabbath of Vision”), the Sabbath that precedes the week in which the tragic day of Tisha B’Av is observed. Even as he stands with the Israelites on the border of the Land of Israel—their journey almost at its end—Moses reminds them how difficult it has been to get them this far. Moses reproves the people, primarily for the sin of the scouts who returned from touring the land of Israel and caused the people to lose faith with their evil report. In fact, the entire first chapter of Deuteronomy speaks of this sin. In the 12th verse of Devarim Moses cries out: "Eicha Esa L'vadi... "How can I bear your trouble, your burden, and your bickering all by myself?!" (How can I carry this alone...)?" (Deut. 1:12). That first word of the verse, "How," has a special resonance this week. In Hebrew it is "Eichah," (pronounced ei-CHAH) and we read Devarim on the Shabbat preceding Tisha B’Av because the word, “Eicha,” recalls the opening verse of the Book of Lamentations, “Eicha yahsh’vah bah’dahd ha’ir?” “Alas, how does the city of Jerusalem sit in solitude.” We will read Lamentations this Monday night on Tisha B’Av. In Hebrew, Lamentations is called Megillat Eichah, "the Scroll of How."

There are two similarities in the phrases: first, the use of the word Eichah (how), second the use of the words L'vad and Badad (both with the same word root) meaning alone. There is a tradition of chanting the verse that begins with this word Eichah "How" in this portion to the same mournful melody used for Lamentations on Tisha B'Av. The Torah readers at my synagogue did just that and we could hear the sadness. For Moses, recalling the sin of the spies which occurred on Tisha B’ Av, is a harbinger of what’s to come—the destruction of the First Temple. And, an echo of the other catastrophes for the Jewish people that are said to have occurred on Tisha B'Av— the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE; the crushing of the Bar Kokhbah Rebellion in 132 CE, the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492; the Holocaust among many others.

So by one Hebrew word we can understand that both Moses' complaint and the book of Lamentations share a sense of despair. How is it that human beings can be so cruel, destructive, and so forgetful of what is right? It is as if Moses foresees the doom that is the destiny of the people he serves. Eventually, their tendency toward complaint and ingratitude will bring about the destruction of the Temple. How can he bear the thought that his life's mission of service to the Israelites—to bring them to the Land of Israel—will be reversed by their own failings?

Maybe this is the point of Tisha B'Av. This day of mourning exists to remind us—at least once a year—not to forget. It reminds us of the terrible price we pay if we do not treat each other with compassion and forgiveness. And in our day, if we allow ruthless killers like Hamas with their philosophy of hatred to triumph. But even with Lamentations mournful cry, we are reminded that with God there remains hope. In the midst of grief we are always reminded to look to the East from whence comes our hope. And to hold out for there will be better days. Tisha B'Av is our annual peek into the abyss of "How?" so that we will remember to be faithful to God and to hope for a better world. It's not about mourning for a building. It's not about wishing for the restoration of animal sacrifices. It is about clinging to hope despite despair. It is about envisioning a reality in which we transcend our human failings.

May that time come, speedily and in our days.